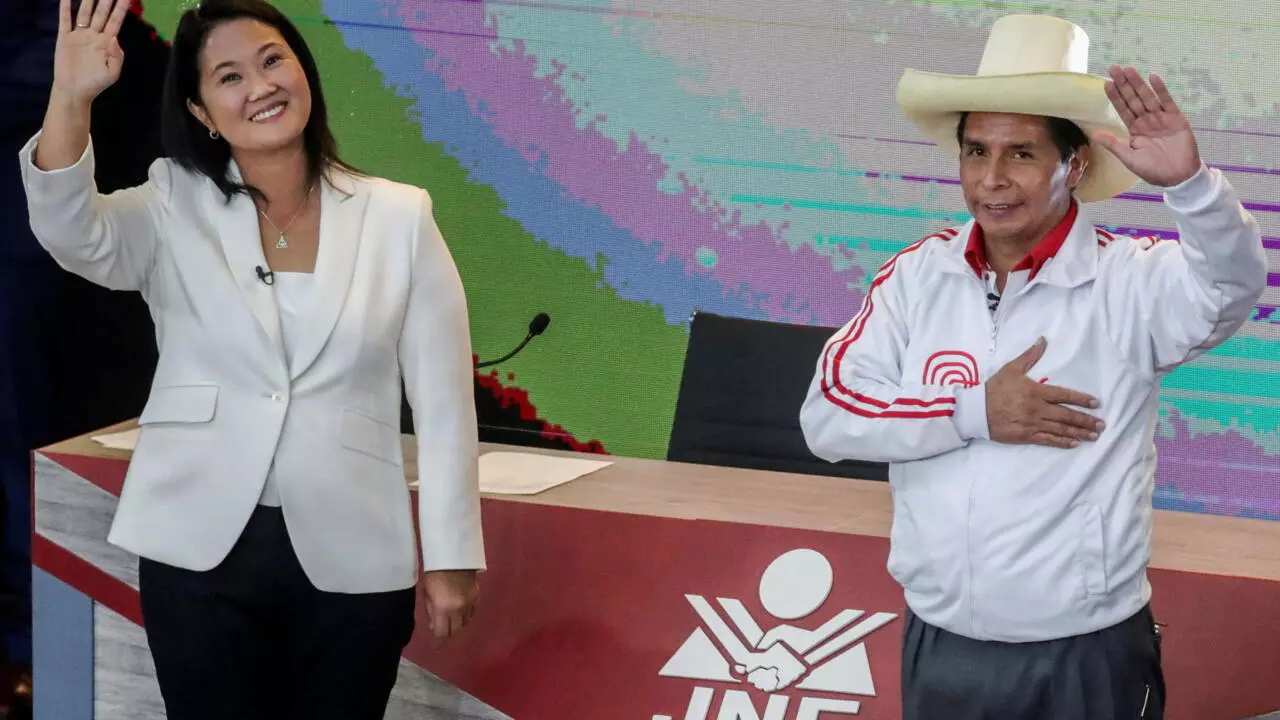

Left-wing candidate Pedro Castillo appears to be headed to victory in one of Peru’s most divisive elections ever. Yet his rival Keiko Fujimori is disputing the count, calling for the nullification of some 300,000 ballots for alleged anomalies, enough to potentially erase the slim 70,000 vote margin of Castillo.

While Fujimori’s allegations have yet to gain widespread support, with international election observers seemingly inclined to give the elections a clean bill of health, the same observers have cautioned against prematurely dismissing the claims.

After saying that they have "observed a positive electoral process" and that the “The Mission has not detected serious irregularities,” observers from the Organization of American States were quick to urge authorities to wait until challenges to the vote have been resolved before calling a winner.

At the very least, many believe that this should prompt Peruvian authorities to initiate reforms to stave off potential crises in similarly tightly contested elections.

The list of complaints, which seem to correspond with known weaknesses of the manual system, include lack of signatures on tallies, arithmetic mistakes, and doubts on whether a vote was properly marked in a ballot.

In a press conference, Fujimori and her lawyers claimed to have discovered proof of forged signatures on more than 500 ballot tallies, plus other anomalies, imputing such on the Free Peru party, to which Castillo belongs.

Experts have long warned against human intervention of any sort in elections, whether the hand counting of ballots or reliance on physical signatures to verify tallies. In recent years, manual elections have increasingly been regarded as being prone to errors, if not outright fraud. In fact, the idea of reducing human intervention has been a powerful impetus behind the shift by countries from manual to automated elections.

Moreover, the number of null votes in this Peruvian election cycle is cause for concern. While a lot of voters might have intentionally left their ballots blank in protest, the potential for disenfranchisement is alarming.

In the last three Peruvian elections (the first round of this year’s presidential and both rounds of the 2016 presidential elections), null votes surpassed 5% of total number of ballots cast. This translates to more than 1 million voters which were potentially disenfranchised because they “marked incorrectly their ballot”. In a contest separated by just 70,000 votes, this could easily spark a crisis.

Even more tellingly, the slow pace of the vote count has created the very conditions for this heightened political tension. While countries which use automation technology regularly expect to know their next leaders just a few hours after the polls close, a week has already passed without the Peru vote having been completely counted.

Peru finds itself at a crossroads -- stay with the flawed manual elections and risk a potentially disastrous outcome down the road, or start exploring ways to modernize its elections and take its fledgling democracy to a new level of stability.